A Collar of Rust

A Collar of Rust

An interview with Collane di Ruggine

by Margaret Killjoy

Ruggine might be the closest thing that SteamPunk Magazine has to a sister publication. Coming out of the Italian radical/squatter scene as SPM had its roots in the US, Ruggine is a journal that sets out to use imagination to challenge the status quo. I was delighted to have a chance to interview two of their writers and editors, and beginning in this issue we will be running the occasional translation of stories from their pages.

SPM: Can you introduce Ruggine to our readers? What does the name mean? What kind of stories do you run?

reginazabo: Ruggine is a fanzine of radical fiction and illustrations. We publish short stories that try to dissect our tragic, pathetic world through irony and imagination, in the belief that metaphors can be sometimes stronger and more convincing than plain, objective, non-fiction essays.

We have a DIY approach to the whole process: our breeding ground is the Italian punk DIY community and the hacker scene, which are widely interconnected since hacker spaces in Italy are often inside squats and social centers. So not only do our authors and illustrators belong to this environment, but also the people who contributed to our graphic layout are at least acquainted with the idea of open-source. Our publications are released with no copyright, or at most under CC licenses, and we also try to use open-source instruments and DIY resources in the graphic layout and distribution: from the open-source software we use for layout (Scribus), to open fonts, to a distribution platform which allows us to find co-producers for our future publications. (Produzioni dal basso, a sort of self-managed Kickstarter ahead of its time.)

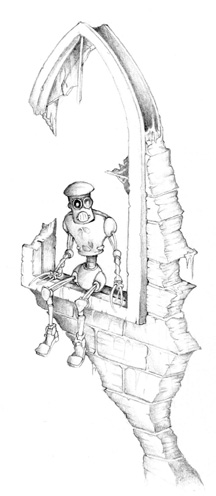

In the beginning we were planning to publish books, and our first publication was a short essay on the relationship between the humankind and technology in the light of J.G. Ballard’s works. As we talked about our future projects, decay always was an object of our reflections, so we decided a good name for our DIY publishing house could be Collane di Ruggine, collane meaning “necklaces,” but also “book series,” and ruggine meaning “rust.” So we had our rusty series, but no long text to publish in a book. Instead, we had a lot of short stories we had written and some others we had found in English on the web and wanted to translate. Switching to a fanzine was immediate, and we didn’t have to think much to decide that it would have illustrations: we wanted something

pleasant, that people would wish to pore through at first glance. The title was immediate as well: if the publisher was called “Rust Book Series,” the magazine could only

be, simply, “Rust.”

Pinche: Ruggine is a small DIY fanzine. We all belong to this weird community made of squatters, hackers, anti-psychiatric activists, punks, and similar creatures. One day we started to reflect on the fact that in this community there is a lot of non-fiction, that we create wonderful music, write amazing theater pieces, and build houses, but don’t produce any fiction. We started to think that our community needed to recreate its imagination, which perhaps had been made too sterile by years of day-to-day struggles and frustrations. Ruggine’s authors are very different people, but somehow they share a passion for “imaginary literature” (we like to use this expression, by Italo Calvino, since it adds a different scope to the idea of science fiction) and love to plunge reality into a

richer dimension. Ruggine never had a determined “editorial line”: we choose the stories we publish by inhaling them, looking for that imaginary atmosphere that goes deep to the heart of the matter even when the plot is about apparently far-away situations. We look for a way of writing that is somehow archetypical, that talks to people in a way that is ironically more direct than a thousand news articles could be.

Rust is one of these archetypes: it is the result of a something that used to be a certain material but is now changing into something else, it is the past turned into future in a painful, beautiful way. We imagine the exploded world of this non-future of ours as a rusty world covered with vegetation.

SPM: What is the steampunk scene like in Italy? What is it like interacting with that scene as radicals? What about the other way around: what kind of response do you get with your fiction from the radical scene?

reginazabo: I don’t know of any “steampunk scene” in Italy: there may be some cos-players, there are a couple of websites, but I’ve never heard about any steampunk

public events. Frankly, the only steampunk parties I’ve been to had been organized by people connected to Collane di Ruggine and therefore to the punk/squatter/hacker scene. I’ve tried to get in touch with some steampunk authors, but I found them a bit disappointing, perhaps because I hadn’t understood yet that steampunk is often definitely not punk, not only in this country. In Italy most steampunk literature is actually genre literature with a Victorian twist, so you’ll have some Victorian fantasy

novels and some Victorian thrillers, but nothing particularly impressive, as far as I know. I find that steampunk has a lot more potentialities, I’ve tried to explain why in my introduction to the Italian translation of A Steampunk’s Guide to Apocalypse, but in short it offers us the possibility to tell our history from a different, radical point of

view, and I’d like to see the literary steampunk scene do a lot more of this.

On the other side, A Steampunk’s Guide to Apocalypse (which wasn’t published by Collane di Ruggine, but came out together with the first issue of Ruggine, containing a

story and illustrations from SPM #1) was a great success in Italy: many people here have learnt about steampunk from this book, and I’m happy that their approach to this

subculture was radicalized straight away, mixing from the beginning the steampunk aesthetics with a punk DIY approach. In the radical scene, we’ve had a good response:

many people send us their stories and invite us to present our project in social centers, but I think this has less to do with steampunk (which is very appreciated nevertheless)

than with our general approach to radical fiction.

Pinche: When we read your vision of steampunk in the pages of the SteamPunk Magazine, we thought that this was what we actually were: strange creatures that are

more punk than steam, and are firm in their decision to reassert the tight bond between both things. But unfortunately we haven’t found this spirit virtually anywhere in Italian realities. I can think of a couple of Italian mad scientists who toil in their dark cellars without knowing that they are ideal steampunks. The few things that exist are

often soaked in (the worst) pop culture, narcissism, and aestheticism, gaudy and not very interesting.

The presentations and reading we do with Ruggine nearly always take place in radical venues, and we have often had positive responses even if we are not very well known. I think there is some resistance to a vision that has so little materialism in it, but there is also a lot of curiosity and a certain sense of liberation in the possibility of using expressive means that go beyond the conventions of the “perfect modern squatter.” [Editor’s note: I

believe Pinche is referring to the “perfect modern squatter” as what is accepted unquestioned by many in Italy to be the most legitimate form of radical activism.]

In the last few years we have regularly participated in the Italian Hackmeeting, where I feel we are perceived as a vibrant part of the community because of the common way in which we look at technique and at self-management, and because of our smiling apocalyptic vision. My aim is to have Ruggine read by the crustiest punk of the suburbia, instead of seeing it circulating in sophisticated readers’ clubs, so I guess I can be pretty

satisfied for the time being.

This interview first appeared in Steampunk Magazine #8