We included this story in a postcard book (PDF) we published in 2009, as part of a campaign against the politics of fear. Back then, the Italian migration policies and media hypes were already creating a shroud of fear around anything that wasn’t “normal”, “regular”, “respectable”, “decent”. And already back then, the government decided that rescuing boats full of migrants that went adrift in the sea should be made illegal. This atmosphere of fear and distrust created the foundations of what is happening today, with refugee camps rising along the borders of our brave new world and dictatorships, campaigns of terror, famines and droughts devastating the rest of the planet.

In the face of all this, we felt the need to translate and republish this story, a dystopic picture of the long-term effects of the way our rich world is treating the human beings who didn’t have the luck to be born among the “rich” and the rest of the world that didn’t happen to be born human.

Category Archives: English

Ghost Ships

Lichens

Translated from Italian by reginazabo

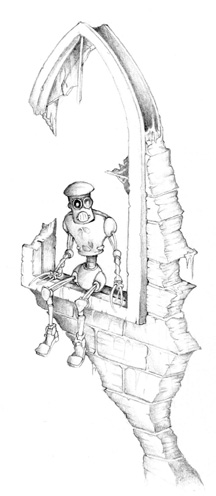

Illustration by Kevin Petty

First Installment

While she walked the tip of her shoes confronted the debris of crushed bricks and dull metal objects. The air was biting cold; she adjusted the collar of her coat to her neck. Just ten minutes before a relentless rain had been dropping, but now the sky seemed at peace and the air cleaned up by the weeping-like outburst. She sniffed the air—all around the ruins smelled like forests. The broken bricks, the splintered concrete blocks, those small asphalt islets that still emerged from beneath the grass.

She got to the Mouthed Gate. It bore that name because what remained of its two iron doors was a pair of large slivers at the top, forming the cheekbones of an open-mouthed face.

It was a marvellous gate, one of her favorite, one of the many that still guarded imaginary palaces and invisible factories. Like the rest of them, the Mouthed Gate was totally useless. It was a mere memory of what it had once protected. And like the rest of them, you would have never dreamt of not using it, of mocking it by going around it.

Sitting on the banister of an orphan window there was Typtri.

“Hallo, Zam.”

“Hi… today there was this slow rain falling instead of the usual neige… have you heard?”

“Mm. Nice. I like rain. Afterwards smells are sharper.”

As Zam got closer, her gaze wandered behind a long line of ants that ran along the banister, each one with its tiny load of debris.

“This place will soon be eaten, just like everything else. I’ll be sorry when the Mouthed Gate won’t exist anymore.”

“Zam, perhaps I have found a place where we could look for your fuse. Down at the bay I heard of an old factory in City22—it produced electronic and hydraulic components. They say that many walls are still standing—in some parts there’s even a roof. I wouldn’t wonder if we found something that is still usable there.”

“It must have been looted…”

“Yeah, sure, but nobody would’ve wanted your fuse… it hasn’t been used since the end of the 20th Century.”

“Don’t know, Typtri. City22 is far away. Sometimes I think that I should give up looking for that damned fuse. I’m just making you all waste a lot of time.”

“Zam, do you seriously think I’ve got something better to do?” Typtri would have smiled, if it had been able to, and Zam appreciated this effort anyway.

“Besides, who knows? At the factory in City22 I might find some oil, or some gears…”

“Yeah, alright. But we must leave tonight—who knows when we’ll have another chance of flying without the neige falling.”

Typtri collapsed down from the banister—with those short legs, it shouldn’t have acted so athletic, and with so much corroded iron around, Zam always feared it would crash into pieces at any moment. It was a funny device,

Typtri was—its looks always contradicted its words.

“Let’s meet at the bay in a couple of hours, then. I just need some time to get a couple of things. I will fetch some oil and water I found yesterday: it should be enough to get us to City22.”

“Okay, Typtri. See you in two hours at the bay.” Continue reading

A Collar of Rust – Interview by Margaret Killjoy

A Collar of Rust

A Collar of Rust

An interview with Collane di Ruggine

by Margaret Killjoy

Ruggine might be the closest thing that SteamPunk Magazine has to a sister publication. Coming out of the Italian radical/squatter scene as SPM had its roots in the US, Ruggine is a journal that sets out to use imagination to challenge the status quo. I was delighted to have a chance to interview two of their writers and editors, and beginning in this issue we will be running the occasional translation of stories from their pages.

SPM: Can you introduce Ruggine to our readers? What does the name mean? What kind of stories do you run?

reginazabo: Ruggine is a fanzine of radical fiction and illustrations. We publish short stories that try to dissect our tragic, pathetic world through irony and imagination, in the belief that metaphors can be sometimes stronger and more convincing than plain, objective, non-fiction essays.

We have a DIY approach to the whole process: our breeding ground is the Italian punk DIY community and the hacker scene, which are widely interconnected since hacker spaces in Italy are often inside squats and social centers. So not only do our authors and illustrators belong to this environment, but also the people who contributed to our graphic layout are at least acquainted with the idea of open-source. Our publications are released with no copyright, or at most under CC licenses, and we also try to use open-source instruments and DIY resources in the graphic layout and distribution: from the open-source software we use for layout (Scribus), to open fonts, to a distribution platform which allows us to find co-producers for our future publications. (Produzioni dal basso, a sort of self-managed Kickstarter ahead of its time.)

In the beginning we were planning to publish books, and our first publication was a short essay on the relationship between the humankind and technology in the light of J.G. Ballard’s works. As we talked about our future projects, decay always was an object of our reflections, so we decided a good name for our DIY publishing house could be Collane di Ruggine, collane meaning “necklaces,” but also “book series,” and ruggine meaning “rust.” So we had our rusty series, but no long text to publish in a book. Instead, we had a lot of short stories we had written and some others we had found in English on the web and wanted to translate. Switching to a fanzine was immediate, and we didn’t have to think much to decide that it would have illustrations: we wanted something

pleasant, that people would wish to pore through at first glance. The title was immediate as well: if the publisher was called “Rust Book Series,” the magazine could only

be, simply, “Rust.”

Pinche: Ruggine is a small DIY fanzine. We all belong to this weird community made of squatters, hackers, anti-psychiatric activists, punks, and similar creatures. One day we started to reflect on the fact that in this community there is a lot of non-fiction, that we create wonderful music, write amazing theater pieces, and build houses, but don’t produce any fiction. We started to think that our community needed to recreate its imagination, which perhaps had been made too sterile by years of day-to-day struggles and frustrations. Ruggine’s authors are very different people, but somehow they share a passion for “imaginary literature” (we like to use this expression, by Italo Calvino, since it adds a different scope to the idea of science fiction) and love to plunge reality into a

richer dimension. Ruggine never had a determined “editorial line”: we choose the stories we publish by inhaling them, looking for that imaginary atmosphere that goes deep to the heart of the matter even when the plot is about apparently far-away situations. We look for a way of writing that is somehow archetypical, that talks to people in a way that is ironically more direct than a thousand news articles could be.

Rust is one of these archetypes: it is the result of a something that used to be a certain material but is now changing into something else, it is the past turned into future in a painful, beautiful way. We imagine the exploded world of this non-future of ours as a rusty world covered with vegetation. Continue reading

Ruggine #1 – Editorial (English translation)

If you think that in times of crisis the best thing you can do is wait, with crossed arms and an empty gaze, for a new miracle that will save us from the abyss where we have fallen, you are unlikely to be interested in reading these pages any further.

If you think that in times of crisis the best thing you can do is wait, with crossed arms and an empty gaze, for a new miracle that will save us from the abyss where we have fallen, you are unlikely to be interested in reading these pages any further.

The economic crisis is just another effect of a system consecrated to collapse, a system that wants us to be scared and resigned, one of the many ghosts that terrify us, neither the first nor the last for sure.

From time immemorial we have wandered among the waste dumps that make up the exhausted geography of a world which is raped every day by progress (another magical world everybody should bow to, until their backs break) – a progress made of death, exploitation, experimentation, devastation and “necessary” reconstruction – and all along we have looked for spare

parts with which we could rethink our lifestyle.

Just as rust modifies metal scraps, giving them new textures and deep warm nuances, our imagination interacts with reality and changes it. The stories you will find in these pages, from the surreal and delicate Licheni [“Lichens”, by pinche] to the claustrophobic nightmare of Occhio sbarrato fiero [“Fierce wide-open eye” by reginazabo], up to the very womb of the codes of law that is depicted in Gravidanza asociale [“Antisocial Pregnancy”, by Alberto Prunetti] (just to mention a few), are all about our present, and challenge the reader to identify it in the various phases of its disfigurement.

A path of signs and designs that follow the metamorphosis of everyday life, translating it into another time-space (weather past or future), and projecting it into another dimension – the dimension of possibility. It is here, in these immaterial transit zones, that our utopias find their place, that our desires take form and voice, that our fears are revealed, because we need to confront and, perhaps, exorcise them. We believe that the reality that surrounds us is not the consequence of an inevitable fate, and that we can therefore distance ourselves from it, laughing at it while taking it seriously, in order to mock its ironies and to build a new reality, starting to imagine it as we keep tilting at nuclear fusion windmills.

Before we close this editorial, we would like to include a manuscript we have found in an old factory that in the meantime has been razed to the ground.

It may have been a steel mill, but we cannot tell for sure, because now it is but one of the many heaps of debris scattered all over our suburbs and our imaginations.

Despatch No. 0

We are the generation of the killed future.

Burnt with phosphorus bombs, poisoned by exhaust gases, starved by a multinational corporation, smothered by a bank, used as a guinea pig by a pharmaceutical industry.

Time, together with our future, has stopped at Nagasaki.

In a strange dimension called “crisis”, “depression”, “negative trend” or “recession”, we live with the certainty that the morsels of future that remain depend solely on ourselves. No pensions, no welfare, no permanent jobs. Governments have nothing else to show but their teeth, and as days go by, the shows of power politics seem more and more unreal.

But after all the future has stopped at Nagasaki and it can restart from there. We will create buyers’ groups to stop eating poisoned food, we will cook with renewable energies, we will use self-management as a lens to watch a newly drawn horizon.

Let the dance begin, let us start rebuilding on ruins – the steps we will take from now on will determine our fate.